So for years I've used Docker Compose as my stepping stone to k8s. If the project is small, or mostly for my own consumption OR if the business requirements don't really support the complexity of k8s, I use Compose. It's simple to manage with bash scripts for deployments, not hard to setup on fresh servers with cloud-init and the process of removing a server from a load balancer, pulling the new container, then adding it back in has been bulletproof for teams with limited headcount or services where uptime is less critical than cost control and ease of long-term maintenance. You avoid almost all of the complexity of really "running" a server while being able to scale up to about 20 VMs while still having a reasonable deployment time.

What are you talking about

Sure, so one common issue I hear is "we're a small team, k8s feels like overkill, what else is on the market"? The issue is there are tons and tons of ways to run containers on virtually every cloud platform, but a lot of them are locked to that cloud platform. They're also typically billed at premium pricing because they remove all the elements of "running a server".

That's fine but for small teams buying in too heavily to a vendor solution can be hard to get out of. Maybe they pick wrong and it gets deprecated, etc. So I try to push them towards a more simple stack that is more idiot-proof to manage. It varies by VPS provider but the basic stack looks like the following:

- Debian servers setup with

cloud-initto run all the updates, reboot, install the container manager of choice. - This also sets up Cloudflare tunnels so we can access the boxes securely and easily. Tailscale also works great/better for this. Avoids needing public IPs for each box.

- Add a tag to each one of those servers so we know what it does (redis, app server, database)

- Put them into a VPC together so they can communicate

- Take the deploy script, have it SSH into the box and run the container update process

Linux updates involve a straightforward process of de-registering, destroying the VM and then starting fresh. Database is a bit more complicated but still doable. It's all easily done in simple scripts that you can tie to github actions if you are so inclined. Docker compose has been the glue that handles the actual launching and restarting of the containers for this sample stack.

When you outgrow this approach, you are big enough that you should have a pretty good idea of where to go now. Since everything is already in containers you haven't been boxed in and can migrate in whatever direction you want.

Why Not Docker

However I'm not thrilled with the current state of Docker as a full product. Even when I've paid for Docker Desktop I found it to be a profoundly underwhelming tool. It's slow, the UI is clunky, there's always an update pending, it's sort of expensive for what people use it for, Windows users seem to hate it. When I've compared Podman vs Docker on servers or my local machines, Podman is faster, seems better designed and just in general as a product is trending in a stronger direction. If I don't like Docker Desktop and prefer Podman Desktop, to me its worth migrating the entire stack over and just dumping Docker as a tool I use. Fewer things to keep track of.

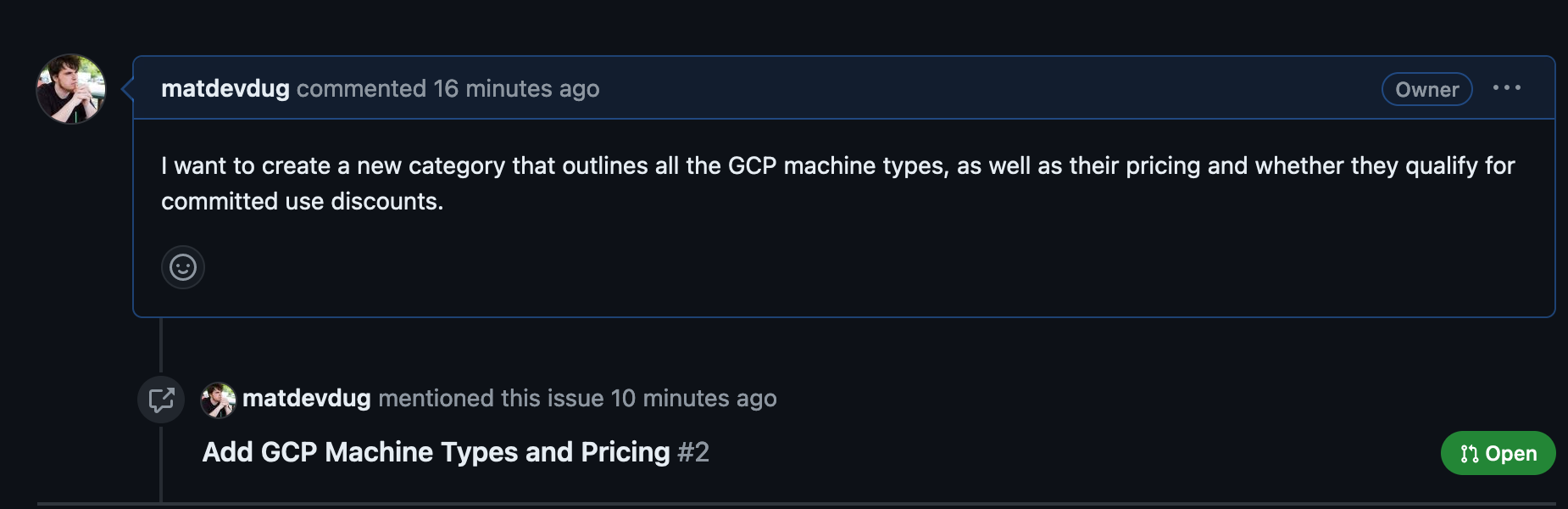

Now the problem is that while podman has sort of a compatibility layer with Docker Compose, it's not a one to one replacement and you want to be careful using it. My testing showed it worked ok for basic examples, but more complex stuff and you started to run into problems. It also seems like work on the project has mostly been abandoned by the core maintainers. You can see it here: https://github.com/containers/podman-compose

I think podman-compose is the right solution for local dev, where you aren't using terribly complex examples and the uptime of the stack matters less. It's hard to replace Compose in this role because its just so straight-forward. As a production deployment tool I would stay away from it. This is important to note because right now the local dev container story often involves running k3 on your laptop. My experience is people loath Kubernetes for local development and will go out of their way to avoid it.

The people I know who are all-in on Podman pushed me towards Quadlet as an alternative which uses systemd to manage the entire stack. That makes a lot of sense to me, because my Linux servers already have systemd and it's already a critical piece of software that (as far as I can remember) works pretty much as expected. So the idea of building on top of that existing framework makes more sense to me than attempting to recreate the somewhat haphazard design of Compose.

Wait I thought this already existed?

Yeah I was also confused. So there was a command, podman-generate-systemd, that I had used previously to run containers with Podman using Systemd. That has been deprecated in favor of Quadlet, which are more powerful and offer more of the Compose functionality, but are also more complex and less magically generated.

So if all you want to do is run a container or pod using Systemd, then you can still use podman-generate-systemd which in my testing worked fine and did exactly what it says on the box. However if you want to emulate the functionality of Compose with networks and volumes, then you want Quadlet.

What is Quadlet

The name comes from this excellent pun:

What do you get if you squash a Kubernetes kubelet?

A quadletActually laughed out loud at that. Anyway Quadlet is a tool for running Podman containers under Systemd in a declarative way. It has been merged into Podman 4.4 so it now comes in the box with Podman. When you install Podman it registers a systemd-generator that looks for files in the following directories:

/usr/share/containers/systemd/

/etc/containers/systemd/

# Rootless users

$HOME/.config/containers/systemd/

$XDG_RUNTIME_DIR/containers/systemd/

$XDG_CONFIG_HOME/containers/systemd/

/etc/containers/systemd/users/$(UID)

/etc/containers/systemd/users/

You put unit files in the directory you want (creating them if they aren't present which I assume they aren't) with the file extension telling you what you are looking at.

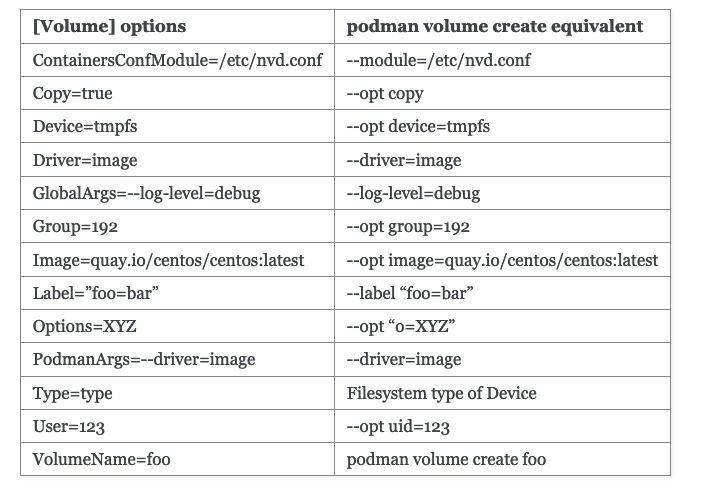

For example, if I wanted a simple volume I would make the following file:

/etc/containers/systemd/example-db.volume

[Unit]

Description=Example Database Container Volume

[Volume]

Label=app=myappYou have all the same options you would on the command line.

You can see the entire list here: https://docs.podman.io/en/latest/markdown/podman-systemd.unit.5.html

Here are the units you can create: name.container, name.volume, name.network, name.kube, name.image, name.build, name.pod

Workflow

So you have a pretty basic Docker Compose you want to replace with Quadlets. You probably need the following:

- A network

- Some volumes

- A database container

- An application container

The process is pretty straight forward.

Network

We'll make this one at: /etc/containers/systemd/myapp.network

[Unit]

Description=Myapp Network

[Network]

Label=app=myappVolume

/etc/containers/systemd/myapp.volume

[Unit]

Description=Myapp Container Volume

[Volume]

Label=app=myapp/etc/containers/systemd/myapp-db.volume

[Unit]

Description=Myapp Database Container Volume

[Volume]

Label=app=myappDatabase

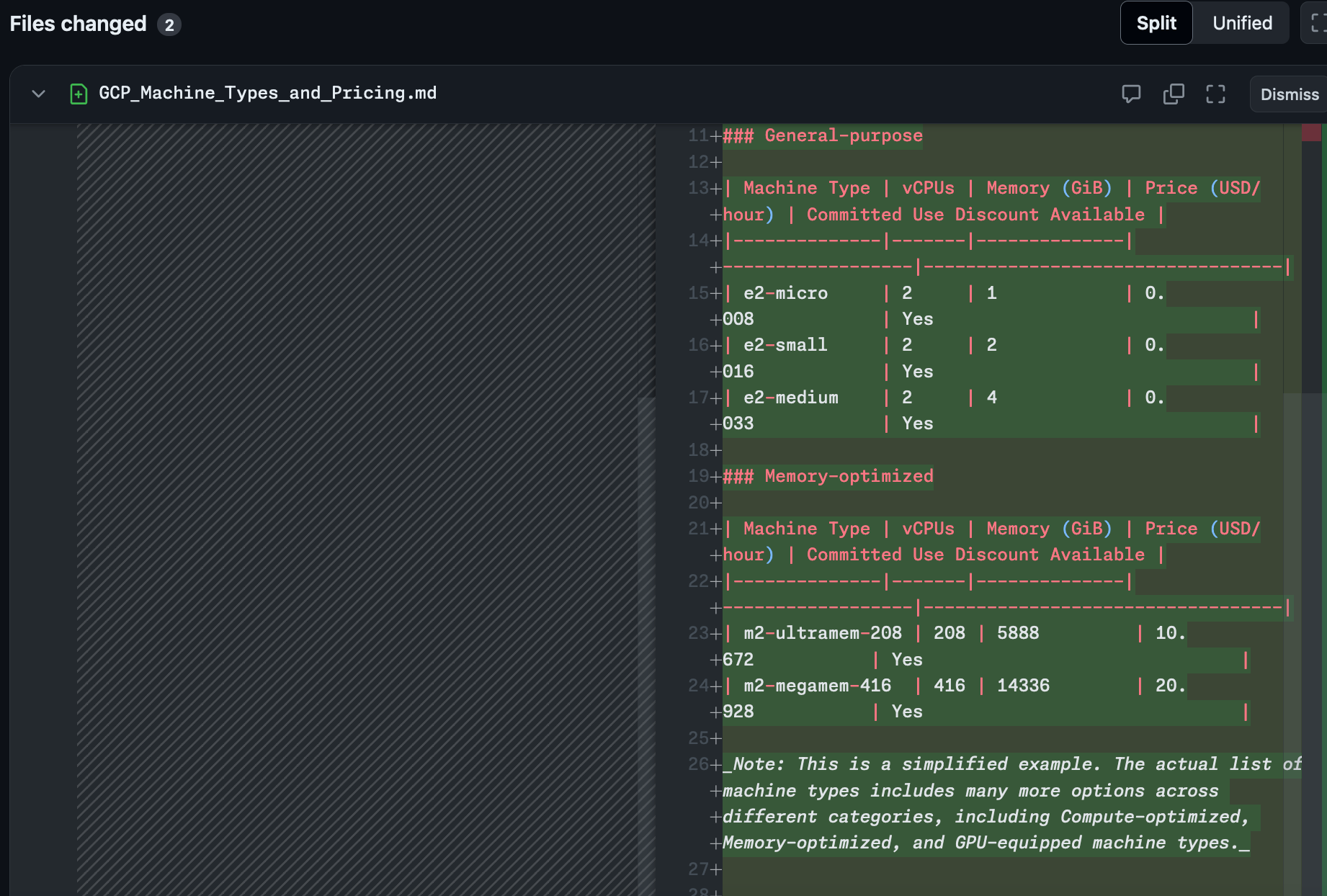

/etc/containers/systemd/postgres.container

[Unit]

Description=Myapp Database Container

[Service]

Restart=always

[Container]

Label=app=myapp

ContainerName=myapp-db

Image=docker.io/library/postgres:16-bookworm

Network=myapp.network

Volume=myapp-db.volume:/var/lib/postgresql/data

Environment=POSTGRES_PASSWORD=S3cret

Environment=POSTGRES_USER=user

Environment=POSTGRES_DB=myapp_db

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target default.targetApplication

/etc/containers/systemd/myapp.container

[Unit]

Description=Myapp Container

Requires=postgres.service

After=postgres.service

[Container]

Label=app=myapp

ContainerName=myapp

Image=wherever-you-get-this

Network=myapp.network

Volume=myapp.volume:/tmp/place_to_put_stuff

Environment=DB_HOST=postgres

Environment=WORDPRESS_DB_USER=user

Environment=WORDPRESS_DB_NAME=myapp_db

Environment=WORDPRESS_DB_PASSWORD=S3cret

PublishPort=9000:80

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target default.targetNow you need to run

systemctl daemon-reloadand you should be able to use systemctl status to check all of these running processes. You don't need to run systemctl enable to get them to run on next boot IF you have the [Install] section defined. Also notice that when you are setting the dependencies (requires, after) that it is called name-of-thing.service, not name-of-thing.container or .volume. It threw me off at first but just wanted to call that out.

One thing I want to call out

Containers support AutoUpdate, which means if you just want Podman to pull down the freshest image from your registry that is supported out of the box. It's just AutoUpdate=registry. If you change that to local, Podman will restart when you trigger a new build of that image locally with a deployment. If you need more information about logging into registries with Podman you can find that here.

I find this very helpful for testing environments where I can tell servers to just run podman auto-update and just getting the newest containers. It's also great because it has options to help handle rolling back and failure scenarios, which are rare but can really blow up in your face with containers without k8s. You can see that here.

What if you don't store images somewhere?

So often with smaller apps it doesn't make sense to add a middle layer of build and storage the image in one place and then pull that image vs just building the image on the machine you are deploying to with docker compose up -d --no-deps --build myapp

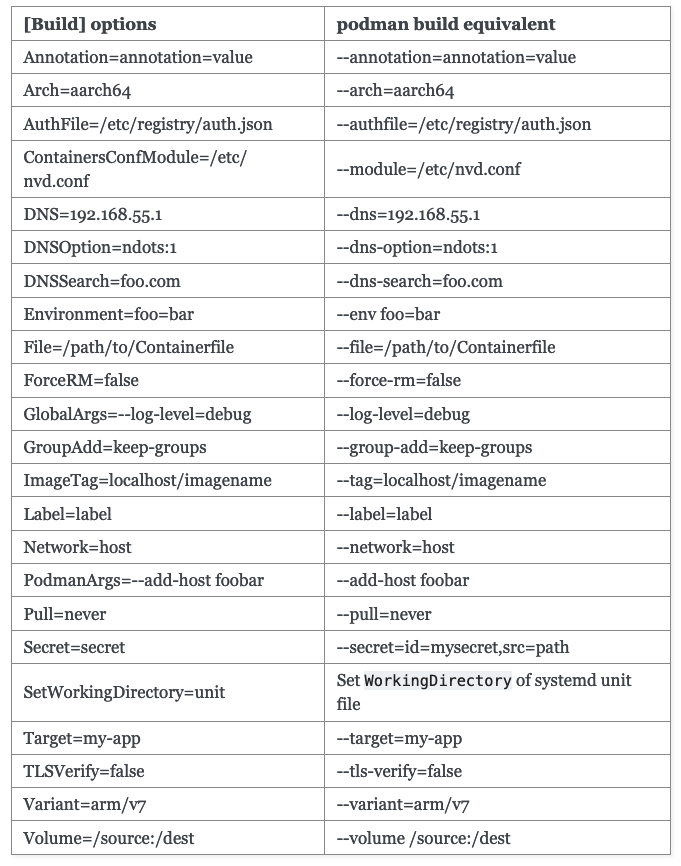

You can do the same thing with Quadlet build files. The unit files are similar to the ones above but with a .build extension and the documentation is pretty simple to figure out how to convert whatever you are looking at to it.

I found this nice for quick testing so I could easily rsync changes to my test box and trigger a fast rebuild with the container layers mostly getting pulled from cache and only my code changes making a difference.

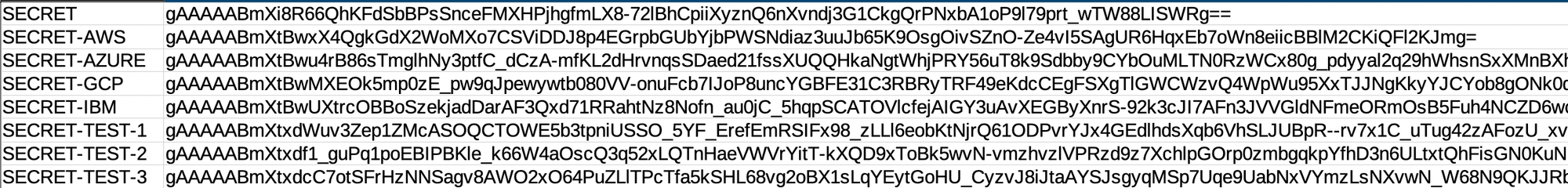

How do secrets work?

So secrets are supported with Quadlets. Effectively they just build on top of podman secret or secrets in Kubernetes. Assuming you don't want to go the Kubernetes route for this purpose, you have a couple of options.

- Make a secret from a local file (probably bad idea):

podman secret create my_secret ./secret.txt - Make a secret from an environmental variable on the box (better idea):

podman secret create --env=true my_secret MYSECRET - Use stdin:

printf <secret> | podman secret create my_secret -

Then you can reference these secrets inside of the .container file with the Secret=name-of-podman-secret and then the options. By default these secrets are mounted to run/secrets/secretname as a file inside of the container. You can configure it to be an environmental variable (along with a bunch of other stuff) with the options outlined here.

Rootless

So my examples above were not rootless containers which are best practice. You can get them to work, but the behavior is more complicated and has problems I wanted to call out. You need to use default.target and not multi-user.target and then also it looks like you do need loginctl enable-linger to allow your user to start the containers without that user being logged in.

Also remember that all of the systemctl commands need the --user argument and that you might need to change your sysctl parameters to allow rootless containers to run on privileged ports.

sudo sysctl net.ipv4.ip_unprivileged_port_start=80Unblocks 80, for example.

Networking

So for rootless networking Podman previously used slirp4netns and now uses pasta. Pasta doesn't do NAT and instead copies the IP address from your main network interface to the container namespace. Main in this case is defined as whatever interface as the default route. This can cause (obvious) problems with inter-container connections since its all the same IP. You need to configure the containers.conf to get around this problem.

[network]

pasta_options = ["-a", "10.0.2.0", "-n", "24", "-g", "10.0.2.2", "--dns-forward", "10.0.2.3"]Also ping didn't work for me. You can fix that with the solution here.

That sounds like a giant pain in the ass.

Yeah I know. It's not actually the fault of the Podman team. The way rootless containers work is basically they use user_namespaces to emulate the privileges to create containers. Inside of the UserNS they can do things like mount namespaces and networking. Outgoing connections are tricky because vEth pairs cannot be created across UserNS boundaries without root. Inbound relies on port forwarding.

So tools like slirp and pasta are used since they can translate Ethernet packets to unprivileged socket system calls by making a tap interface available in the namespace. However the end result is you need to account for a lot of potential strangeness in the configuration file. I'm confident this will let less fiddly as time goes on.

Podman also has a tutorial on how to get it set up here: https://github.com/containers/podman/blob/main/docs/tutorials/rootless_tutorial.md which did work for me. If you do the work of rootless containers now you have a much easier security story for the rest of your app, so I do think it ultimately pays off even if it is annoying in the beginning.

Impressions

So as a replacement for Docker Compose on servers, I've really liked Quadlet. I find the logging to be easier to figure out since we're just using the standard systemctl commands, checking status is also easier and more straightforward. Getting the rootless containers running took....more time than I expected because I didn't think about how they wouldn't start by default until the user logged back in without the linger work.

It does stink that this is absolutely not a solution for local-dev for most places. I prefer that Podman remains daemonless and instead hooks into the existing functionality of Systemd but for people not running Linux as their local workstations (most people on Earth) you are either going to need to use the Podman Desktop Kubernetes functionality or use the podman-compose and just be aware that it's not something you should use in actual production deployments.

But if you are looking for something that scales well, runs containers and is super easy to manage and keep running, this has been a giant hit for me.

Questions/comments/concerns: https://c.im/@matdevdug