In my hometown in Ohio, church membership was a given for middle-class people. With a population of 8,000 people, somehow 19 churches were kept open and running. A big part of your social fabric were the kids who went to the same church that you did, the people you would gravitate towards in a new social situation. The more rural and working class your family was, the less likely you actually went to a church on a regular basis. You'd see them on Christmas and Easter, but they weren't really part of the "church group".

My friend Mark was in this group. His family lived in an underground house next to their former motorcycle shop that had closed down when his dad died. It was an hour walk from my house to his through a beautiful forest filled with deer. I was often stuck within eyesight of the house as a freight train slowly rolled through in front of me, sitting on a tree stump until the train passed. The former motorcycle shop had a Dr. Pepper machine in front of the soaped windows I had a key to and we'd sneak in to explore the shop on sleepovers while his mom worked one of her many jobs.

She was a chain-smoker who rarely spoke, often lighting one cigarette with the burning cherry of the first as she drove us to the local video store to rent a videogame. Mark's older brother also lived in the house, but rarely left his room. Mostly it was the two of us bouncing around unsupervised, watching old movies and drinking way too much soda as his German Shepard wheezed and coughed in the cigarette smoke filled house.

Families like this were often targeted by Evangelical Christians, groups that often tried to lure families in with offers of youth groups that could entertain your kids while you worked. At some point, one of the youth pastors convinced Mark's mom that she should send both of us to his church. Instead of Blockbuster, we got dropped off in front of an anonymous steel warehouse structure with a cross and a buzzing overhead light on a dark country road surrounded by cornfields. Mark hadn't really been exposed to religion, with his father and mother having been deep into biker culture. I had already seen these types of places before and was dreading what I knew came next.

When we walked in, we were introduced to "Pastor Michael", who looked a bit like if Santa Claus went on an extreme diet and bought serial killer glasses. Mark bounced over and started asking him questions, but I kept my distance. I had volunteered the year before to fix up an old train station which involved a large crew of youth "supervised" by the fundamentalist Christian church that wanted to turn the train station into a homeless shelter. We slept on the floors of the middle school in this smaller town neighboring mine, spending our days stripping paint and sanding floors and our evenings being lectured about the evils of sex and how America was in a "culture war". In retrospect I feel like there should have been more protective gear in removing lead paint as child labor, but I guess that was up to God.

After one of these long sessions where we were made to stand up and promise we wouldn't have sex before we got married, I made a joke in the walk back to our assigned classroom and was immediately set upon by the senior boy in the group. He had a military style haircut and he threw me against a locker hard enough that I saw stars. I had grown up going to Catholic school and mass every Sunday, spending my Wednesday nights going to CCD (Confraternity of Christian Doctrine), which was like Sunday school for Catholics. All of this was to say I had pretty established "Christian" credentials. This boy let me know he thought I was a bad influence, a fake Christian and that I should be careful since I'd be alone with him and his friends every night in the locked classroom. The experience had left me extremely wary of these Evangelical cults as I laid silently in my sleeping bag on the floor of a classroom, listening to a hamster running in a wheel that had clearly been forgotten.

To those of you not familiar with this world, allow me to provide some context. My Catholic education presented a very different relationship with holy figures. God spoke directly to very few people, saints mostly. There were many warnings growing up about not falling into the trap of believing you were such a person, worthy of a vision or a direct conversation with a deity. It was suggested softly this was more likely mental illness than divine intervention. He enters your heart and changes your behavior and gives you peace, but you aren't in that echelon of rare individuals for whom a chat was justified. So to me these Evangelicals claiming they could speak directly with God was heresy, a gross blasphemy where random "Pastors" were claiming they were saints.

The congregation started to file in and what would follow was one of the most surreal two hours of my life. People I knew, the woman who worked at the library and a local postal worker started to scream and wave their arms, blaming their health issues on Satan. Then at one point Scary Santa Claus started to shake and jerk, looking a bit like he was having a seizure. He started to babble loudly, moving around the room and I stared as more and more people seemed to pretend this babbling meant something and then doing it themselves. The bright lights and blaring music seemed to have worked these normal people into madness.

In this era before cell phones, there wasn't much I could do to leave the situation. I waited and watched as Mark became convinced these people were channeling the voice of God. "It's amazing, I really felt something in there, there was an energy in the room!" he whispered to me as I kept my eyes on the door. One of the youth pastors asked me if I felt the spirit moving through me, that I shouldn't resist the urge to join in. I muttered that I was ok and said I had to go to the bathroom, then waited in the stall until the service wrapped up almost two hours later.

In talking to the other kids, I couldn't wrap my mind around the reality that they believed this. "It's the language of God, only a select few can understand what the Holy Spirit is saying through us". The language was all powerful, allowing the Pastor to reveal prophesy to select members of the Church and assist them with their financial investments. This was a deadly serious business that these normal people completely believed, convinced this nonsense jabbering that would sometimes kind of sound like language was literally God talking through them.

I left confident that normal, rational people would never believe such nonsense. These people were gullible and once I got out of this dead town I'd never have to be subjected to this level of delusion. So imagine my surprise when, years later, I'm sitting in an giant conference hall in San Francisco as the CEO of Google explains to the crowd how AI is the future. This system that stitched together random words was going to replace all of us in the crowd, solve global warming, change every job. This was met with thunderous applause by the group, apparently excited to lose their health insurance. All this had been kicked off with techno music and bright lights, a church service with a bigger budget.

Every meeting I went to was filled with people ecstatic about the possibility of replacing staff with this divine text generator. A French venture capitalist who shared a Uber with me to the original Google campus for meetings was nearly breathless with excitement. "Soon we might not even need programmers to launch a startup! Just a founder and their ideas getting out to market as fast as they can dream it." I was tempted to comment that it seemed more likely I could replace him with an LLM, but it felt mean. "It is going to change the world" he muttered as we sat in a Tesla still being driven by a human.

It has often been suggested by religious people in my life that my community, the nonreligious tech enthusiasts, use technology as a replacement for religion. We reject the fantastical concept of gods and saints only to replace them with delusional ideas of the future. Self-driving cars were inevitable until it became clear that the problem was actually too hard and we quietly stopped talking about it. Establishing a colony on Mars is often discussed as if it is "soon", even if the idea of doing so far outstrips what we're capable of doing by a factor of 10. We tried to replace paper money with a digital currency and managed to create a global Ponzi scheme that accelerated the destruction of the Earth.

Typically I reject this logic. Technology, for its many faults, also produces a lot of things with actual benefits which is not a claim religion can make most of the time. But after months of hearing this blind faith in the power of AI, the comparisons between what I was hearing now and what the faithful had said to me after that service was eerily similar. Is this just a mass delusion, a desperate attempt by tech companies to convince us they are still worth a trillion dollars even though they have no new ideas? Is there anything here?

Glossolalia

Glossolalia, the technical term for speaking in tongues, is an old tradition with a more modern revival. It is a trademark of the Pentecostal Church, usually surrounded by loud music, screaming prayers and a leader trying to whip the crowd into a frenzy. Until the late 1950s it was confined to a few extreme groups, but since then has grown into a more and more common fixture in the US. The cultural interpretation of this trend presents it as a “heavenly language of the spirit” accessible only to the gifted ones. Glossolalists often report an intentional or spontaneous suspension of will to convey divine messages and prophecies.

In the early 1900s W. J. Seymour, a minister in the US, started to popularize the practice of whipping his congregation into a frenzy such that they could speak in tongues. This was in Los Angeles and quickly became the center of the movement. For those who felt disconnected from religion in a transplant city, it must have been quite the experience to feel your deity speaking directly through you.

It's Biblical basis is flimsy at best however. Joel 2:28-9 says:

And afterwards I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, young men will see visions. Even on my servants, both men and women, I will pour out my Spirit in those days.

A lot of research has been done into whether this speech is a "language", with fascinating results. In the Psychology of Speaking in Tongues, Kildahl and Qualben attempted to figure that out. Their conclusions were that while it could sound like a language, it was a gibberish, closer to the fake language children use to practice the sounds of speaking. To believers though, this presented no problems.

He argued that glossolalia is real and that it is a gift from the Holy Spirit. He argued that a person cannot fake tongues. Tongues are an initial evidence of the spirit baptism. It is a spiritual experience. He observed that tongues cannot be understood by ordinary people. They can only be understood spiritually. He noted that when he speaks in tongues he feels out of himself. The feeling is very strange. One can cry, get excited, and laugh. As our respondent prayed, he uttered: Hiro---shi---shi---sha---a---karasha. He jumped and clapped his hands in excitement and charisma. He observed that if God allows a believer to speak in tongues there is a purpose for that. One can speak in tongues and interpret them at the same time. However, in his church there is no one who can interpret tongues. According to our respondent, tongues are intended to edify a person. Tongues are beneficial to the person who speaks in tongues. A person does not choose to pray in tongues. Tongues come through the Spirit of God. When speaking in tongues, it feels as if one has lost one's memory. It is as if one is drunk and the person seems to be psychologically disturbed. This is because of the power of the influence of the Holy Spirit. Tongues are a special visitation symbolising a further special touch of the Holy Spirit. Source

In reality glossolalic speech is not a random and disorganized production of sounds. It has specific accents, intonations and word-like units that resembles the original language of the speaker. [source] That doesn't make it language though, even if the words leave the speaker feeling warm and happy.

What it actually is, at its core, is another tool the Evangelical machine has at its disposal to use the power of music and group suggestion to work people into a frenzy.

The tongue-speaker temporarily discards some of his or her ego functioning as it happens in such times as in sleep or in sexual intercourse.41 This phenomenon was also noticed in 2006 at the University of Pennsylvania, USA, by researchers under the direction of Andrew Newburg, MD who completed the world's first brain-scan study of a group of Pentecostal practitioners while they were speaking in tongues. The researchers noticed that when the participants were engaged in glossolalia, activity in the language centres of the brain actually decreased, while activity in the emotional centres of the brain increased. The fact that the researchers observed no changes in any language areas, led them to conclude that this phenomenon suggests that glossolalia is not associated with usual language function or usage.

It's the power of suggestion. You are in a group of people and someone, maybe a plant, kicks it off. You are encouraged to join in and watch as your peers enthusiastically get involved. The experience has been explained as positive, so of course you remember it as a positive experience, even if in your core you understand that you weren't "channeling voices". You can intellectually know it is a fake and still feel moved by the experience.

LLMs

LLMs, large language models, which have been rebranded as AI, share a lot with the Evangelical tool. AI was classically understood to be a true artificial intelligence, a thinking machine that actually processed and understood your request. It was seen as the Holy Grail of computer science, the ability to take the best of human intellect and combine it into an eternal machine that could guide and help us. This definition has leaked from the sphere of technology and now solidly lives on in Science Fiction, the talking robot who can help and assist the humans tasked with something.

If that's the positive spin, then there has always been a counter argument. Known as the "Chinese room argument" as shorthand, it says that a digital computer running code cannot have a mind, understanding or consciousness. You can create a very convincing fake though. The thought experiment is as follows:

You've made a computer that behaves as if it understands Chinese. It takes Chinese characters as input and returns Chinese characters as output. It does so at such a high level that it passes the Turing test in that a native Chinese speaker believes the thing it is speaking to is a human being speaking Chinese. But the distinction is that the machine doesn't understand Chinese, it is simulating the idea of speaking Chinese.

Searle suggests if you put him into a room with an English version of the program he could receive the same characters through a slot in the door, process them according to the code and produce Chinese characters as output, without understanding anything that is being said. However he still wouldn't speak or understand Chinese.

This topic has been discussed at length by experts, so if you are interested in the counterarguments I suggest the great site by Stanford: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-room/

What Is An AI?

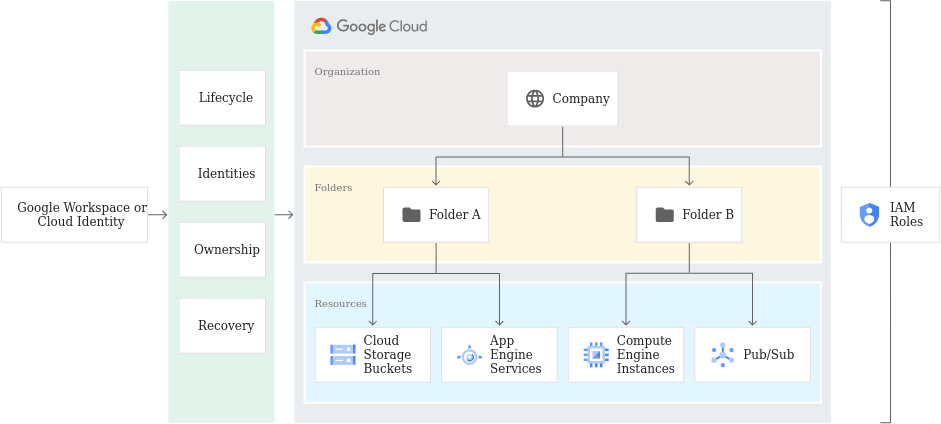

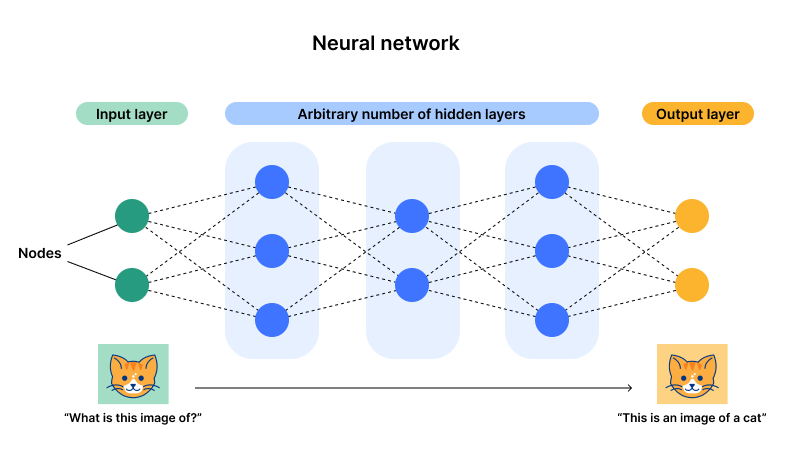

The Neural Networks powering AI at a high level look as follows:

The magic part of AI is the Transformer neural network, which uses self-attention to process not just the elements of text on their own but the way the data relates to each other. It has been fed enough examples to be able to take the input and produce a likely output. Effectively by ingesting every work spoken by humans on video or written on the internet, it can predict with some level of accuracy what a common collection of words to return to a query is.

The end result is a box that consumes a frightening amount of electricity to mimic the responses of an all-knowing eternal AI. The believers can commune directly with this machine spirit, asking it questions and getting back blocks of text or pictures that sometimes look like something a human would make. You cannot question the model or work backwards to determine how specifically it came to the conclusion it did. There is an element of the divine in the process, a specter of magic.

Hallucination

As AI was introduced, we were cautioned to be on the lookout for "hallucinations", where the model would produce convincing-looking fakes. The problem with this warning is it both flies in the face of how humans work (we're not amazing at questioning authoritative-sounding answers) and also suggested this was a temporary problem. But the more you read about AI, you realize it can never solve the hallucination problem because it would need to understand what is "real" and "fake" in order to do that.

What do I mean on a practical level? So I thought I would test out the Google Gemini AI with some easy questions. I had recently written a bash script to query GCP cloud deployments to get their status and write them to markdown. This should be an easy test of the system, right? It's Google AI writing a simple script using the Google CLI to interact with the Google Cloud Platform. Closed ecosystem, high degree of confident, should have definite sources of truth.

Can you write a bash script using the gcloud CLI to query the status of all deployments using cloud deploy, a GCP service, in the GCP project test123 and output the name and current name to a markdown file for each one?

#!/bin/bash

# Set project ID

PROJECT_ID="test123"

# Output directory for markdown files

OUTPUT_DIR="deployment_statuses"

# Create output directory if it doesn't exist

mkdir -p "$OUTPUT_DIR"

# Get all deployments

deployments=$(gcloud deploy deployments list --project "$PROJECT_ID" --format="value(NAME)")

# Loop through each deployment

for deployment in $deployments; do

# Get deployment details

deployment_details=$(gcloud deploy deployments describe "$deployment" --project "$PROJECT_ID" --format="yaml")

# Parse name and state from YAML output

name=$(echo "$deployment_details" | yq .name)

state=$(echo "$deployment_details" | yq .status.state)

# Create markdown file for deployment

output_file="$OUTPUT_DIR/$name.md"

echo "# Deployment: $name" > "$output_file"

echo "Current State: $state" >> "$output_file"

# Add additional information to markdown file as needed (e.g., rollout strategy, create time)

# ...

done

echo "Deployment statuses written to markdown files in $OUTPUT_DIR"

Looks great right? Exactly what I wanted. Except it doesn't work.

gcloud doesn't have a gcloud deploy deployments argument.

NAME

gcloud deploy - create and manage Cloud Deploy resources

SYNOPSIS

gcloud deploy GROUP | COMMAND [GCLOUD_WIDE_FLAG ...]

DESCRIPTION

Create and manage Cloud Deploy resources.

GCLOUD WIDE FLAGS

These flags are available to all commands: --help.

Run $ gcloud help for details.

GROUPS

GROUP is one of the following:

automation-runs

Manages AutomationRuns resources for Cloud Deploy.

automations

Manages Automations resources for Cloud Deploy.

custom-target-types

Create and manage Custom Target Type resources for Cloud Deploy.

delivery-pipelines

Create and manage Delivery Pipeline resources for Cloud Deploy.

job-runs

Manages job runs resources for Cloud Deploy.

releases

Create and manage Release resources for Cloud Deploy.

rollouts

Create and manage Rollout resources for Cloud Deploy.

targets

Create and manage Target resources for Cloud Deploy.Now I know this because I wrote it, but there's no way someone looking at this with no knowledge of the gcloud CLI would understand why this wouldn't work.

I tried again, this time with a simpler question. Maybe because not that many people use gcloud it doesn't have a big enough sample size to construct a real answer. Let's ask a more basic question, but let's keep it on Google technology. Kubernetes has been documented to death, books written about it, millions of articles and blog posts. Certainly that will work.

How do I, in hosted Kubernetes on GCP, write a deployment configuration yaml which sets nodeAffinity using preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution. The nodepool should be nodes02 with a weight of one.

What I'm trying to prompt it here is to give me back a configuration file not with nodeSelector but with Node Affinity, the softer preference level for assigning pods to nodes. But there's a small trick in the question. I want a deployment not a Pod spec. This is a distinction which requires a more nuanced comprehension of the subject matter, the ability to not pull the most common example but the more specific example. What we want is this:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: nginx-deployment

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nginx

replicas: 3

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

affinity:

nodeAffinity:

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- weight: 1

preference:

matchExpressions:

- key: cloud.google.com/gke-nodepool

operator: In

values:

- nodes02

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.7.9

ports:

- containerPort: 80What I got back was this:

spec:

nodeSelector:

cloud.google.com/gke-nodepool: nodes02

affinity:

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- weight: 1

matchExpressions:

- key: cloud.google.com/gke-nodepool

operator: In

values:

- nodes02The problem with this response is it does a very different thing from the thing I was trying to do. nodeSelector is a stricter approach, ensuring pods are only scheduled on nodes that match the label. nodeAffinity is a much softer preference, telling k8s I'd like the pods to go there if possible but if that isn't possible, put them where you would normally do.

Both of these examples seem reasonable. The machine responded with something that could be construed as the answer, a clever parody of human intelligence, but ultimately it is more like a child playing. It doesn't understand the question, but understands how to construct convincing looking fakes.

To the faithful though, this isn't a problem.

However, if the training data is incomplete or biased, the AI model may learn incorrect patterns. This can lead to the AI model making incorrect predictions, or hallucinating.

For example, an AI model that is trained on a dataset of medical images may learn to identify cancer cells. However, if the dataset does not include any images of healthy tissue, the AI model may incorrectly predict that healthy tissue is cancerous. This is an example of an AI hallucination.

[Source]

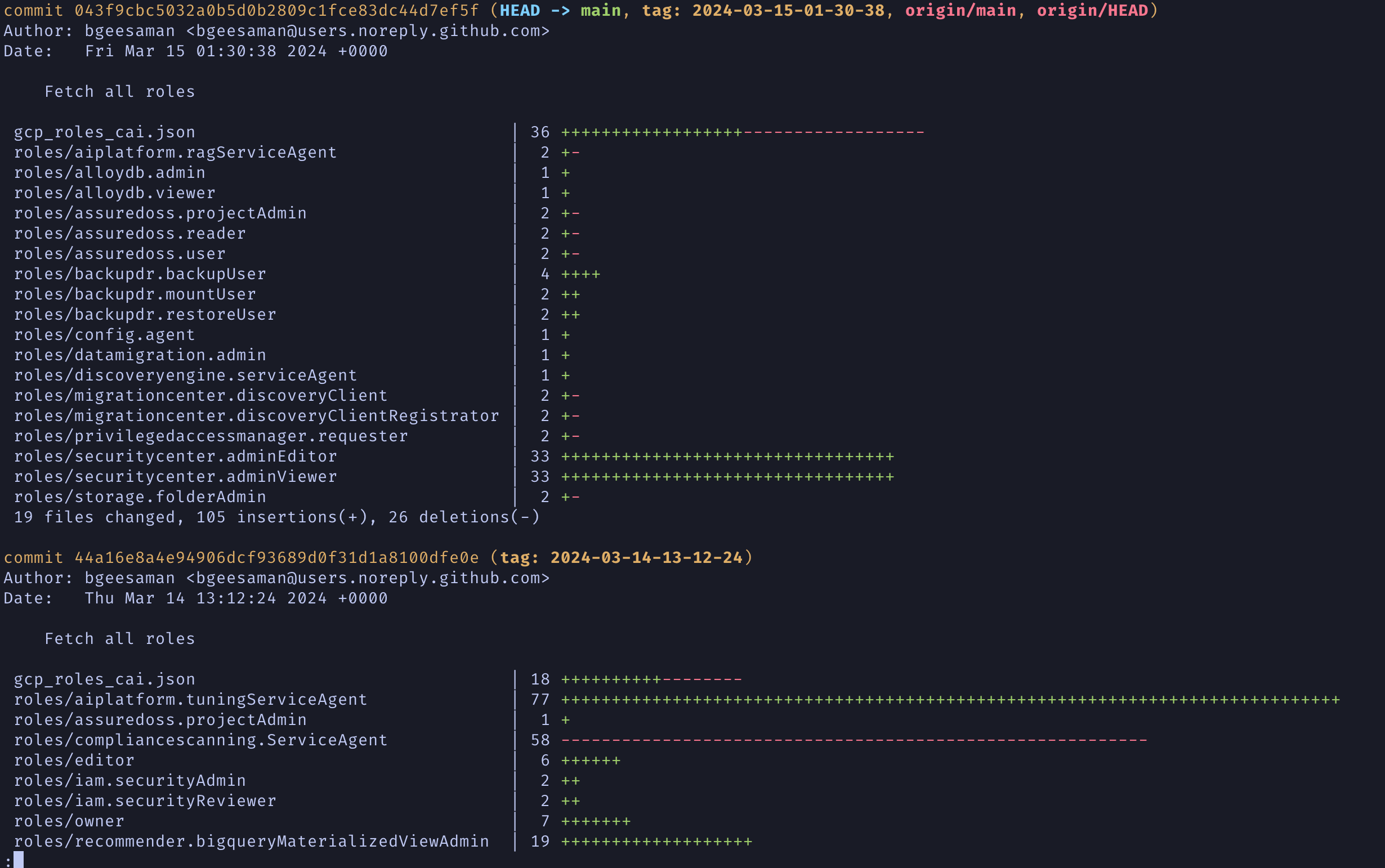

This creates a false belief that the problem lies with the training data, which for both of my examples simply cannot be true. Google controls both ends of that equation and can very confidently "ground" the model with verifiable sources of information. In theory this should tether their output and reduce the chances of inventing content. It reeks of a religious leader claiming while that prophecy was false, the next one will be real if you believe hard enough. It also moves the responsibility for the problem from the AI model to "the training data", which for these LLMs represents a black box of information. I don't know what the training data is, so I can't question whether its good or bad.

Is There Anything Here?

Now that isn't to say there isn't amazing work happening here. LLMs can do some fascinating things and the transformer work has the promise to change how we allow people to interact with computers. Instead of an HTML form with strict validation and obtuse error messages, we can instead help explain to people in real-time what is happening, how to fix problems, just in general provide more flexibility when dealing with human inputs. We can have a machine look at less-sorted data and find patterns, there are lots of ways for this tech to make meaningful differences in human life.

It just doesn't have a trillion dollars worth of value. This isn't a magic machine that will replace all human workers, which for some modern executives is the same as being able to talk directly to God in terms of the Holy Grail of human progress. Finally all the money can flow directly to the CEO himself, cutting out all those annoying middle steps. The demand of investors for these companies to produce something new has outstripped their ability to do that, resulting in a dangerous technology being unleashed upon the world with no safeties. We've made a lying machine that doesn't show you its work, making it even harder for people to tell truth from fiction.

If LLMs are going to turn into actual AI, we're still years and years from that happening. This represents an interesting trick, a feel-good exercise that, unless you look too closely, seems like you are actually talking to an immortal all-knowing being that lives in the clouds. But just like everything else, if your faith is shaken for even a moment the illusion collapses.

Questions/comments/concerns: https://c.im/@matdevdug