One amusing thing about following tech news is how often the tech community makes a bold prediction or assertion, only to ultimately be completely wrong. This isn't amusing in a "ha ha, we all make mistakes" kind of way. It's amusing in the way that watching someone confidently stride into a glass door is amusing. You feel bad, but also, they really should have seen that coming.

Be it VR headsets that would definitely replace reality by 2018, or self-driving cars in every driveway "within five years" (a prediction that has been made every five years since 2012), we have a remarkable talent for making assumptions about what consumers will like and value without having spent a single goddamn minute listening to those same consumers. It's like a restaurant critic reviewing a steakhouse based entirely on the menu font.

So when a friend asked me what I thought about "insert new revolutionary technology that will change everything" this week, my brain immediately jumped to "it'll be like 3D printers and Warhammer." This comparison made sense in the moment, as we were currently playing a game of Warhammer 40,000, surrounded by tiny plastic soldiers and the faint musk of regret. But I think, after considering it later, it might make sense for more people as well—a useful exercise in tech enthusiasm versus real user wants and needs.

Or, put another way: a cautionary tale about people who have never touched grass telling grass-touchers how grass will work in the future.

Miniatures and Printers

One long-held belief among tech bros has been the absolute confidence that 3D printers would, at some point, disrupt. Exactly what they would disrupt wasn't 100% clear. Disruption, in Silicon Valley parlance, is less a specific outcome and more a vibe—a feeling that something old and profitable will soon be replaced by something new and unprofitable that will somehow make everyone rich. A common example trotted out was one of my favorite hobbies: tabletop wargaming. More specifically, the titan of the industry, Warhammer 40,000.

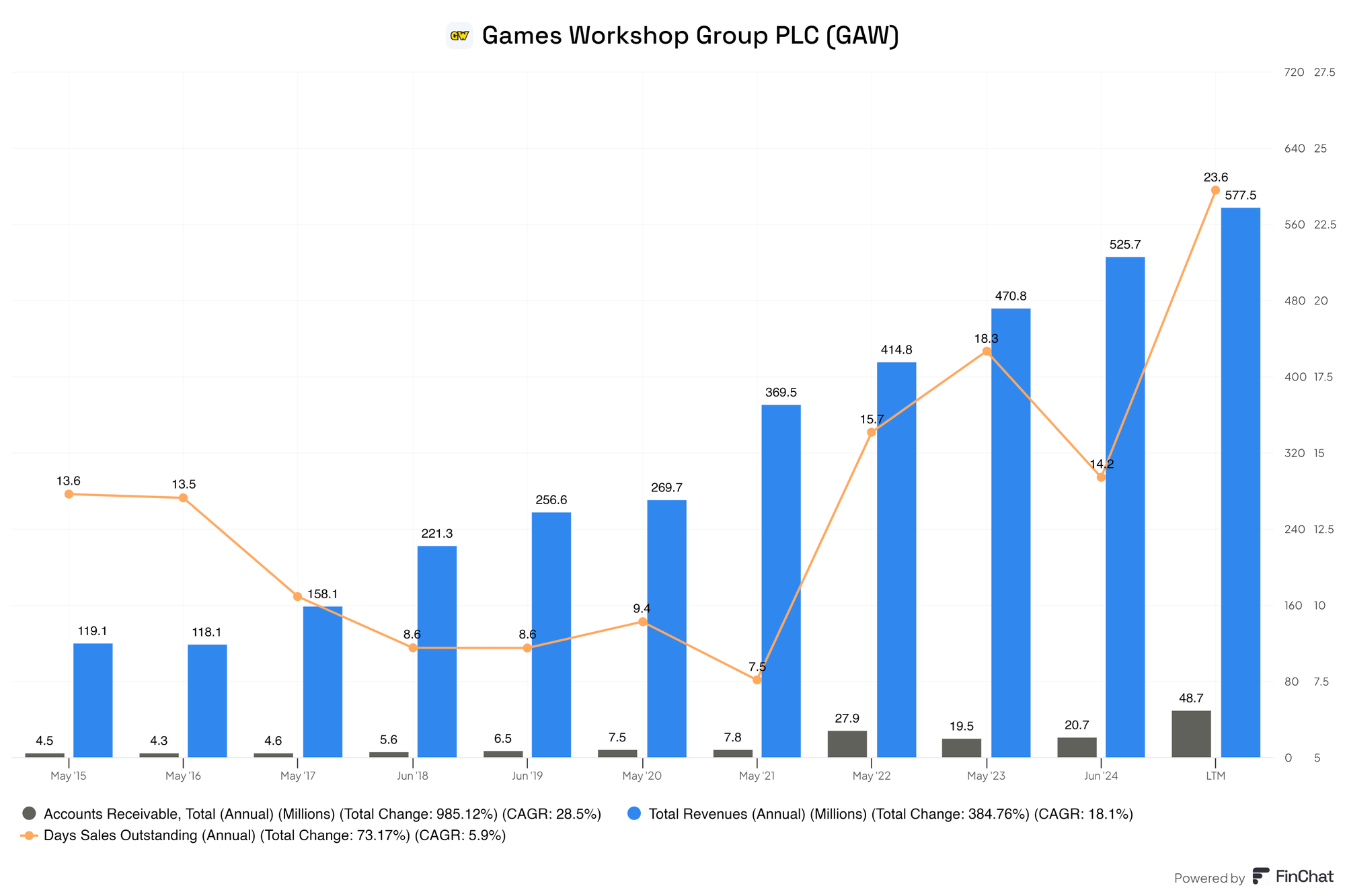

Every time a new 3D printer startup graced the front page of Hacker News, this proclamation would echo from the comments section like a prophecy from a very boring oracle: "This will destroy Games Workshop." Reader, it has not destroyed Games Workshop. Games Workshop is doing fine. Games Workshop will be selling overpriced plastic crack to emotionally vulnerable adults long after the sun has consumed the Earth.

For those who had friends in high school—and I'm not being glib here, this is a genuine demographic distinction—40k is a game where two or more players invest roughly $1,000 to build an army of small plastic figures. You then trim excess plastic with a craft knife (cutting yourself at least twice, this is mandatory), prime them, paint them over the course of several months, and then carefully transport them to an LGS (local game shop) in foam-lined cases that cost more than some people's luggage.

Another fellow dork will then play you on a game board roughly the size of a door, covered in fake terrain that someone spent 40 hours making to look like a bombed-out cathedral. You will both have rulebooks with you containing as many pages as the Bible and roughly as open to interpretation. Wars have been started over less contentious texts.

To put 40k in some sort of nerd hierarchy, imagine a game shop. At the ground level of this imaginary shop are Magic: The Gathering and Pokémon TCG games. Yes, these things are nerdy, but it's not that deep into the swamp. It's more of a gentle wade. You start with Pokémon at age 10, burn your first Tool CD at 14, and then sell your binder of 'mons to fund your Magic habit. This is the natural order of things.

Deeper into the depths, maybe only playing at night like creatures who have evolved beyond the need for vitamin D, are your TTRPGs (tabletop RPGs). The titan of the industry is Dungeons & Dragons, but there is always some new hotness nipping at its heels, designed by someone who thought D&D wasn't quite complicated enough. TTRPGs are cheap to attempt to disrupt—you basically need "a book"—so there are always people trying. These are the folks with thick binders, sacks of fancy dice made from materials that should not be made into dice, and opinions about "narrative agency."

Near the bottom, almost always in the literal basement of said shop, are the wargame community. We are the Morlocks of this particular H.G. Wells situation.

I, like a lot of people, discovered 40k at a dark time in my life. My college girlfriend had cheated on me, and I had decided to have a complete mental breakdown over this failed relationship that was doomed well before this event. The cheating was less a cause and more a symptom, like finding mold on bread that was already stale. Honestly, in retrospect, hard to blame her. I was being difficult. I was the kind of difficult where your friends start sentences with "Look, I love you, but..."

Late at night, I happened to be driving my lime green Ford Probe past my local game shop. The Ford Probe, for those unfamiliar, was a car designed by someone who had heard of cars but had never actually seen one. It was the automotive equivalent of a transitional fossil. I loved it the way you love something that confirms your worst suspicions about yourself.

There, through the shop window, I saw people hauling some of the strangest items out of their trunks. Half-destroyed buildings. Thousands of tiny little figures. Giant robots the size of a small cat with skulls for heads. One man was carrying what appeared to be a ruined spaceship made entirely of foam and spite.

I pulled over immediately.

The owner, who knew me from playing Magic, seemed neither surprised nor pleased to see me. This was his default state. Running a game shop for 20 years will do that to a person. "They're in the basement," he said, in the mostly dark game shop, the way someone might say "the body's in the basement" in a very different kind of establishment.

I descended the rickety wooden stairs to a large basement lit by three naked bulbs hanging from cords. The aesthetic was "serial killer's workspace" meets "your uncle's unfinished renovation project." It was perfect.

Before me were maybe a dozen tables littered with plastic. Some armies had many bug-like things, chitinous and horrible. Others featured little skeletons or robots. There were tape measures everywhere and people throwing literal handfuls of small six-sided dice at the table with the intensity of gamblers who had nothing left to lose. Arguments broke out over millimeters. Someone was consulting a rulebook with the desperation of a lawyer looking for a loophole.

I was hooked immediately.

40k is the monster of wargaming specifically because of a few genius decisions by Games Workshop, the creators—a British company that has somehow figured out how to print money by selling plastic and lore about a fascist theocracy in space. It's a remarkable business model.

- The game looks more complicated to play than it is. Especially now, in the 10th edition, the core rules don't take long to learn. However, there is a lot of depth to the individual options available to each army that take a while to master. So it hits that sweet spot of being fast to onboard someone onto while still providing frightening amounts of depth if you're the kind of person who finds "frightening amounts of depth" appealing rather than exhausting. I am that kind of person. This explains a lot about my life.

- The community is incredible. When I moved from Chicago to Denmark, it took me less than three days to find a local 40k game. Same thing when I moved from Michigan to Chicago. The age and popularity of the game means it is a built-in community that follows you basically around the world. Few other properties have this kind of stickiness. It's like being a Deadhead, except instead of following a band, you're following a shared delusion that tiny plastic men matter. They do matter. Shut up.

- Cool miniatures. They look nice. They're fun to paint and put together. They're complicated without being too annoying. This is the part that 3D printers are supposed to help with.

The Proxy Problem

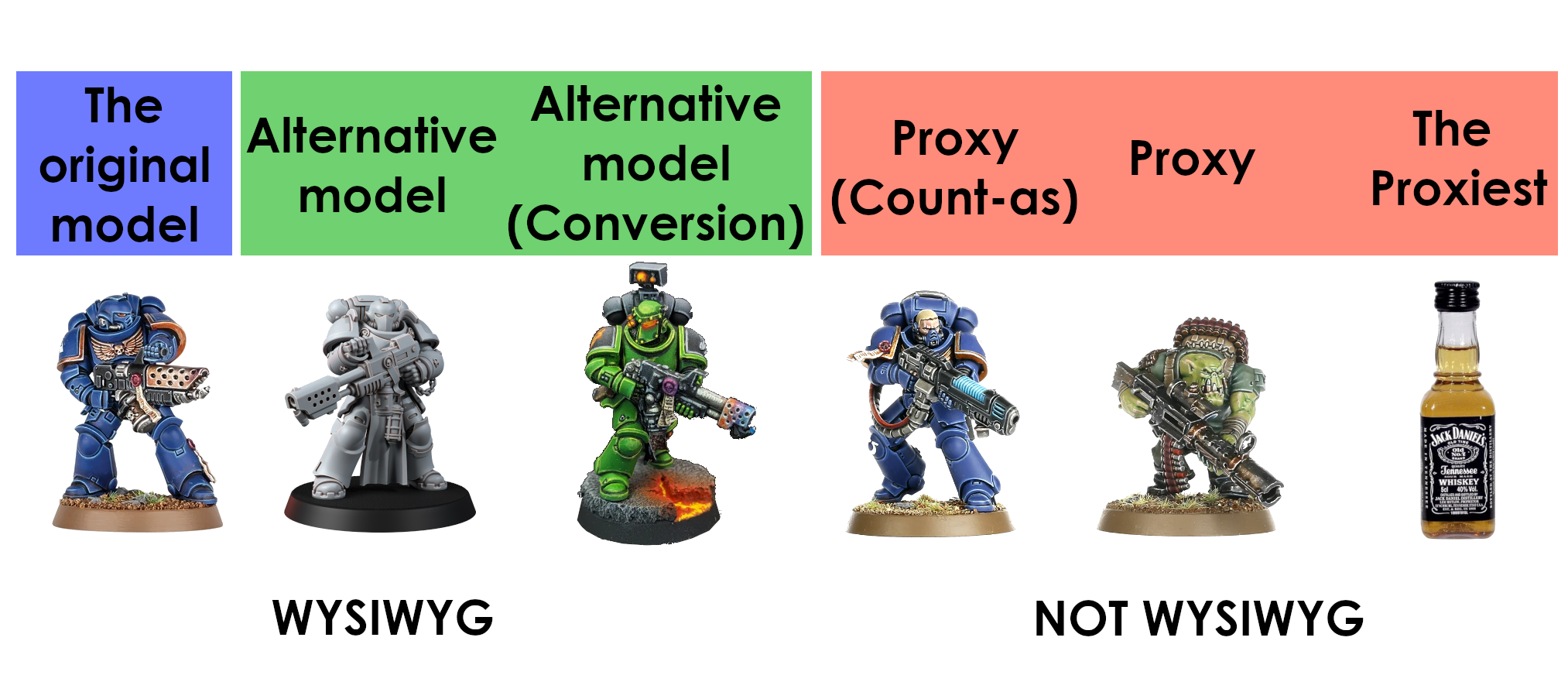

Since the beginning of the game, 40k casual games have allowed proxies. Proxies are stand-ins for specific units that you need for an army but don't have. Why don't you have them? Excellent question. Let me tell you about Games Workshop's relationship with its customers.

Games Workshop has always played a lot of games with inventory. Often releases will have limited supply, or there are weird games with not fulfilling the entire order that a game shop might make. Even when they switched from metal to plastic miniatures, the issues persisted. This has been the source of conspiracy theories since the very beginning—whispers of artificial scarcity, of deliberate shortages designed to create FOMO among people who were already deeply susceptible to FOMO because they collect tiny plastic soldiers.

Whether the conspiracy theories are true is almost beside the point. The feeling of scarcity is real, and feelings, as any therapist will tell you, are valid. Even the stupid ones.

So players had proxies. Anything from a Coke can to another unit entirely. Basically, if it had the same size base and roughly the same height, most people would consider it allowable. "This empty Red Bull can is my Dreadnought." Sure. Fine. We've all been there.

This is where I first started to see 3D-printed miniatures enter the scene.

Similar to most early tech products, the first FDM 3D-printed miniatures I saw were horrible. The thick, rough edges and visible layer lines were not really comparable to the professional product, even from arm's length. They looked like someone had described a Space Marine to a printer that was also drunk. But they were totally usable as a proxy and better than a Coke can. The bar, as they say, was low.

But the technology continued to get better and cheaper and, as predicted by tech people, I started to notice more and more interest in 3D printing among people at the game stores. When I first encountered a resin 3D-printed army at the table, I'll admit I was intrigued. This person had basically fabricated $3,000 worth of hard-to-get miniatures out of thin air and spite.

This was supposed to be the big jumping-off point. The inflection moment. There were a lot of discussions at the table about how soon we wouldn't even have game shops with inventory! They'd be banks of 3D printers that we would all effortlessly use to make all the minis we wanted! The future was here, and it smelled like resin fumes!

3D Printing Misses

Printing a bunch of miniatures off a resin 3D printer quickly proved to have a lot of cracks in this utopian plan. Even a normal-sized mini took hours to print. That wouldn't be so bad, except these printers couldn't just live anywhere in your apartment. They're not like a Keurig. You can't just put them on your kitchen counter and forget about them.

When I was invited to watch someone print off minis with a resin 3D printer, it reminded me a lot of the meth labs in my home state of Ohio. And I don't mean that as hyperbole. I mean there were chemicals, ventilation hoods, rubber gloves, and a general atmosphere of "if something goes wrong here, it's going to go very wrong." The guy giving me the tour had safety goggles pushed up on his forehead. He was wearing an apron. At one point, he said the phrase "you really don't want to get this on your skin" with the casual tone of someone who had definitely gotten it on his skin.

In practice, the effort to get the STL files, add supports, wash off the models with isopropyl alcohol, remove supports without snapping off tiny arms, and finally cure the mini in UV lights was exponentially more effort than I'm willing to invest. And I say this as someone who has painted individual eyeballs on figures smaller than my thumb. I have a high tolerance for tedious bullshit. This exceeded it.

Why?

Before I start, I first want to say I don't dislike the 3D printing community. I think it's great they're supporting smaller artists. I love that they found a hobby inside of a hobby, like those Russian nesting dolls but for people who were already too deep into something. I will gladly play against their proxy armies any day of the week.

But people outside of the hobby proclaiming that this is the "future" are a classic example of how they don't understand why we're doing the activity in the first place. It's like watching someone who has never cooked explain how meal replacement shakes will eliminate restaurants. You're not wrong that it's technically more efficient. You're just missing the entire point of the experience.

The reason why Games Workshop continues to have a great year after year—despite prices that would make a luxury goods executive blush, despite inventory issues, despite a rulebook that changes often enough to require a subscription service—is because of this fundamental misunderstanding.

Players invest a lot of time and energy into an army. You paint them. You decorate the plastic bases with fake grass and tiny skulls. You learn their specific rules and how to use them. You develop opinions about which units are "good" and which are "trash" and you will defend these opinions with the fervor of a religious convert. Despite the eternal complaints about the availability of inventory, the practical reality is that most people can only keep a pipeline of one or maybe two armies going at once.

The bottleneck isn't acquiring plastic. The bottleneck is everything else.

So let's do the math on this. You buy a resin 3D printer. All the supplies. You get a spot in your house where you can safely operate it—which means either a garage, a well-ventilated spare room, or a relationship-ending negotiation with whoever you live with. You find or buy all the STLs you need. Let's say they all have supports in the files, so you just need to print them off. Best-case scenario.

Let's say we break even around 50-75 infantry and a few larger models. This is over the raw cost of materials, but we need to factor in the space in your house it takes up, plus there's a learning curve with figuring out how to do it. You also need to invest a lot of time getting these files for printing and finding the good ones. For the sake of keeping this simple, let's just assume the actual printing process goes awesome. No failed prints. No supports that fuse to the model. No discovering that your file was corrupted after six hours of printing. Fantasy land.

Here's the thing: getting the raw plastic minis is not the time-consuming part.

First, you need to paint them. I take about two hours to paint each model, and I'm far from the best painter out there. I'm solidly in the "looks good from three feet away" category, which is also how I'd describe my general appearance. Vehicles take longer because they're bigger—maybe 10-20 hours for one of those. We're talking somewhere in the ballpark of 150 hours to paint everything that you need to paint for a standard army.

Now don't get me wrong, I love painting. But I'm a 38-year-old with a child and a full-time job. Finding 150 hours for anything that isn't work, childcare, or sleep requires the kind of calendar Tetris that would make a project manager weep. It is a massive investment of time to get an army on the table, even if you remove the financial element of buying the minis entirely.

Frankly, the money I pay to Games Workshop is the easiest part of the entire process. Often the box will be lovingly stacked on top of other sealed mini boxes—a pile of shame, we call it—until I can start the process of even hoping to catch up. I have boxes I bought during the Obama administration. They're still sealed. They judge me.

But okay, let's say we get them all painted. What's next?

Next comes "learn how the army works." There is a ton of flexibility to each army in 40k and how they work and operate. It takes a bit of research and time to figure out what they all do, which is something you are 100% expected to know cover to cover when you show up to play. It's not my job to know what your army can and cannot do. If you show up not knowing your own rules, you will be eaten alive, and you will deserve it.

So what I saw with the 3D printing crowd felt a lot like the "Year of the Linux Desktop" crowd. Every year they would proclaim that soon we'd all get on board with their vision. They would print off an incredibly impressive army with all the hard-to-find minis that were sold once at a convention in 1997. They'd get the army "painted" to some definition of painted—and I'm using those quotation marks with malice—get on the table, and then play effectively that one army the same as the rest of us.

The printer didn't give them more time. It didn't give them more skill. It just gave them more unpainted plastic, which, brother, I have plenty of already.

For those in the 3D printing crowd who weren't big into playing, just painting, part of the point is showing off your incredible work to everyone else. Except nobody wants to see a 3D-printed forgery of an official model. It's like showing up to a car show with a kit car that looks like a Ferrari. Sure, it's impressive in its own way, but it's not really a Ferrari, and everyone knows it, and now we're all standing around pretending we don't know it, and it's uncomfortable for everyone.

Once someone figured out one of your minis was 3D printed, shops generally wouldn't feature it in their display cases. So there was no reason for people who were going to put in 10+ hours per model to skip paying for the official real models. If you're going to invest that much time, you want the real thing. You want the little Games Workshop logo on the base. You want to be able to say "yes, I paid $60 for this single figure" with the quiet dignity of someone who has made peace with their choices.

"Well then the shops can just sell the STLs and do the printing there!"

This shows me you haven't spent a lot of time in these shops.

Game shops need to carry a ton of inventory all the time, and a lot of their sales are impulse purchases. I see a mini I wouldn't typically be interested in, but it's done and ready, and I'm weak, and now I own it. That's the business model. They also operate on relatively thin margins—these aren't Apple Stores, they're labors of love run by people who got into this because they loved games and are now slowly being crushed by commercial rent and distributor minimums.

It's just not feasible for them to print minis on demand and have enough staff to keep an eye on all the printing. Plus, tabletop wargaming isn't their major revenue generator anyway—it's card games like Pokémon and Magic. The wargamers in the basement are a bonus, not the main attraction. We're the weird cousins who show up to Thanksgiving and everyone tolerates us because we're family.

The Moral of the Story

At the end of the day, the 3D printing proclamation that it would disrupt my hobby ended up being a whole lot of nothing. A series of reasonable mistakes were made by people enthusiastic about the technology, resulting in the current situation where every year is the year that all of this will get disrupted. Any day now. Just you wait.

They looked at the price of miniatures and saw inefficiency. They looked at the scarcity and saw opportunity. What they didn't see was that the price and the scarcity were almost beside the point. The hobby isn't about acquiring plastic. The hobby is about what you do with the plastic after you acquire it. The hobby is about the 150 hours of painting. The hobby is about the arguments over rules interpretations. The hobby is about descending into a basement lit by three naked bulbs and finding your people.

You can't 3D print that.

So the next time someone tells you that some new technology is going to "disrupt" something you love, ask yourself: do they actually understand why people love it? Do they understand the irrational, inefficient, deeply human reasons people engage with this thing? Or are they just looking at a spreadsheet and seeing numbers that don't make sense to them?

Because if it's the latter, you can probably ignore them. They'll be wrong. They're almost always wrong.

In the meantime, you can find me in the basement, losing match after match, surrounded by tiny plastic soldiers I've spent hundreds of hours painting, playing a game that makes no sense to anyone who hasn't given themselves over to it completely.

It's not efficient. It's not optimized. It's not disrupting anything.